Excerpt taken from U.S. Army Medical Department Office of Medical History, Chapter 24, pages 632—633

Base Hospital No. 5 took over British General Hospital No. 13 at Boulogne, France

BASE HOSPITAL NO. 5

Base Hospitai No. 5 was organized in February, 1916, at the Harvard University, and was mobilized in May, 1917. The unit left New York May 11, 1917, on the Saxonia and arrived at Falmouth, England, May 22, 1917, and at Boulogne, France on May 30, 1917. It was assigned to the British Expeditionary Force in France and was ordered to take over British General Hospital No. 11.

This hospital was situated between the towns of Dannes and Camiers, Department Pas de Calais. It functioned there until November 1, 1917, when it was transferred to Boulogne sur Mer, where it took over and operated British General Hospital No. 13.

While at Dannes-Camiers, Base Hospital No. 5 frequently was attacked by enemy aircraft, and on the night of September 4, 1917, suffered several casualties. Lieut. William T. Fitzsimons, M. C., was killed, Lieuts. Rae W. Whidden, Thaddeus D. Smith, and Clarence A. McGuire, M. C., were wounded. Lieutenants Whidden and Smith subsequently died. Three enlisted men were killed and five severely wounded; one nurse and 22 patients were wounded. These deaths were the first among the American Expeditionary Forces clue to enemy activity.

The hospital occupied a large municipal building, the bed capacity of which was 650. During its activity, June 1, 1917, to January 20, 1919, this hospital cared for 45,837 patients, both surgical and medical. Of this number 41,015 were British and 4,822 Americans. The greatest number of patients admitted in one day was 964.

The unit was relieved from duty with the British on January 20, 1919, and sailed from Brest, France, April 7, 1919, on the Graf Wafdersee, arriving at New York April 20, 1919. The unit was demobilized May 2, 1919, at Camp Devens, Mass.

PERSONNEL

COMMANDING OFFICER

- Col. Robert U. Patterson, M. C., May 5, 1917, to February 27, 1918.

- Lieut. Col. Roger I. Lee, M. C., February 28, 1918, to September 6, 1918.

- Maj. Henry Lyman, M. C., September 7, 1918, to demobilization.

CHIEF OF MEDICAL SERVICE

- Lieut. Col. Roger I. Lee, M. C. Maj. Reginald Fitz, M. C.

CHIEF OF SURGICAL SERVICE

- Lieut. COI. Horace Binney, M. C.

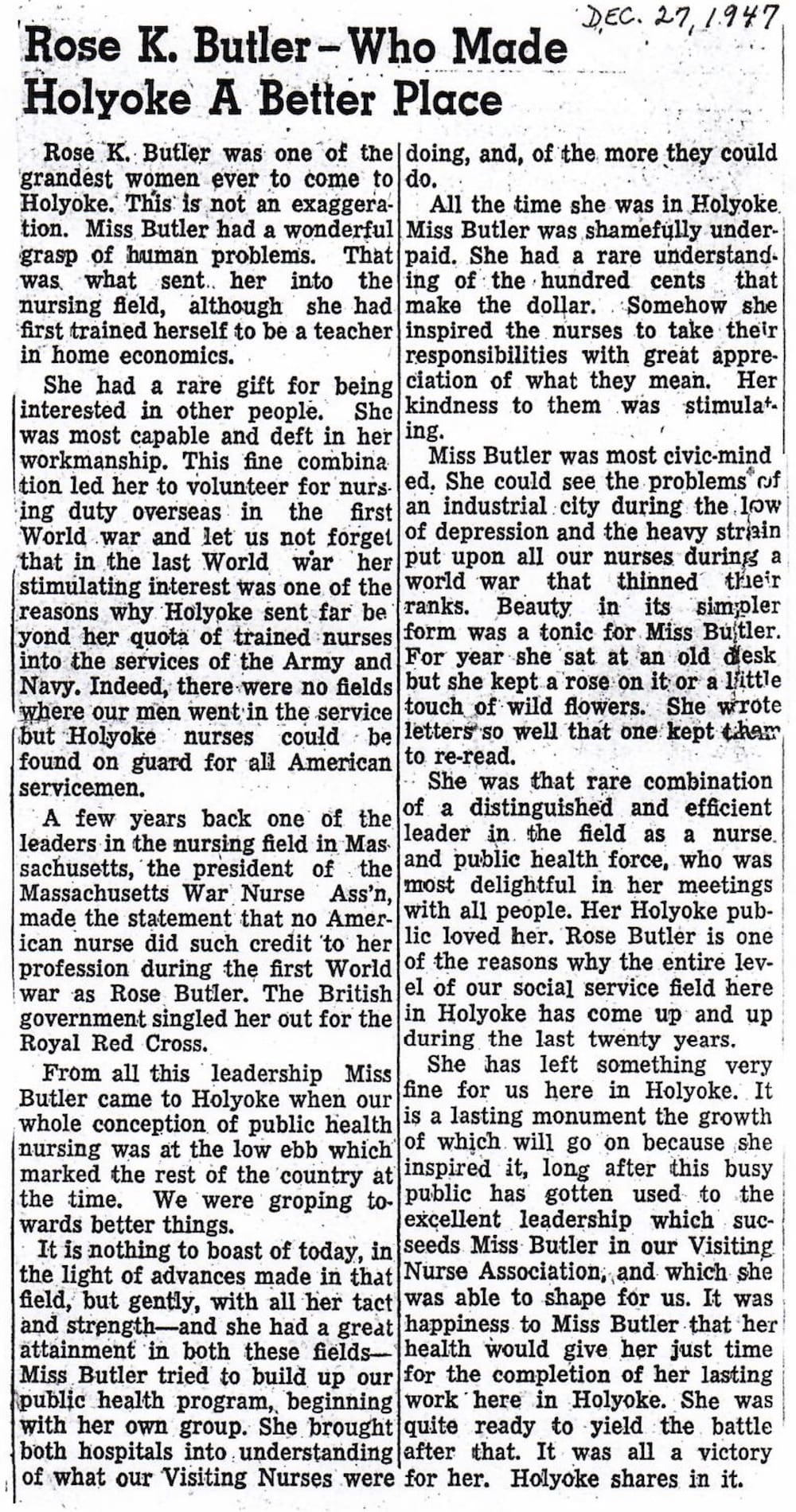

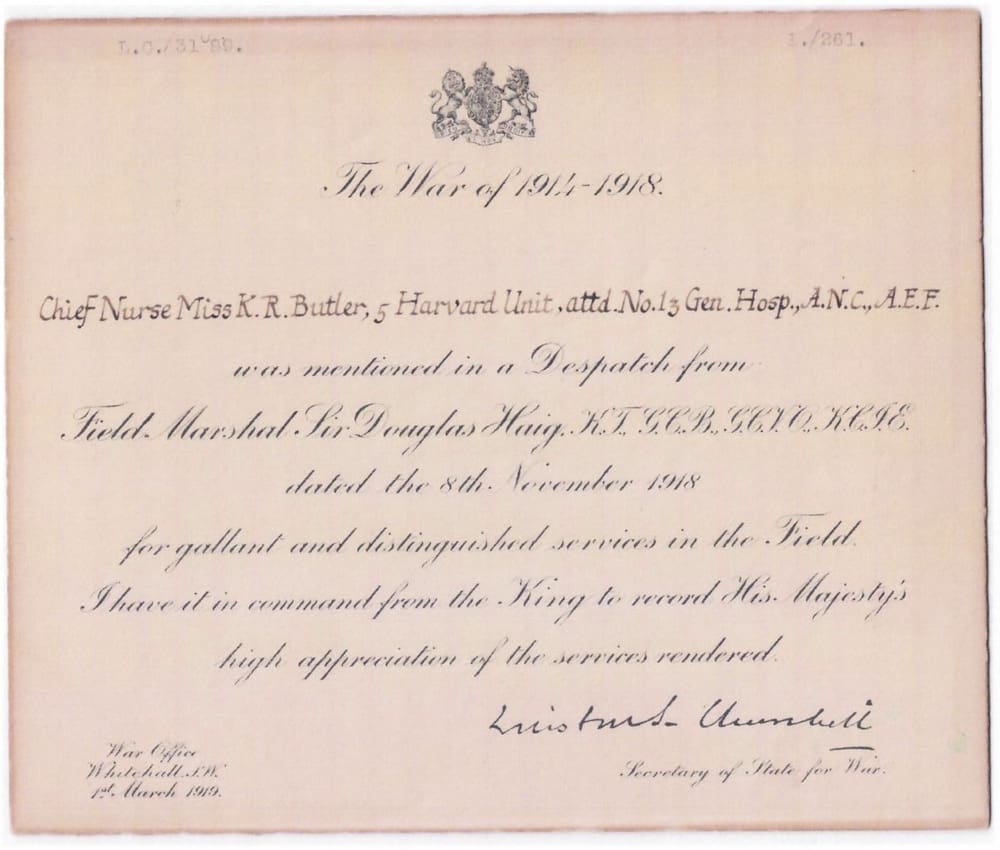

Rose K. Butler

She served as an Army nurse at Base Hospital No. 5 in France during the height of World War I. At the end of the war she was mentioned in a dispatch personally given to her by Field Marshall Douglas Haig.

Excerpt from Base Hospital No. 5 history published by the Barton Press, Boston

Rose K. Butler assistant editor

On the evening of September 2 [1917] some excitement was experienced in camp when German airplanes made a successful raid on Boulogne.

As a signal of warning, at the approach of enemy aircraft, the electric lights would give two short flashes and then be extinguished until danger was passed.

To the uninitiated reader, it may be of interest to know how the approach of the enemy planes is detected. Every one has heard at some time the droning of a gasoline or electric motor and is aware that different motors have different vibrations. Allied and enemy planes were accordingly tuned differently. At several points in the rear of the lines there were tuning forks adjusted to detect the vibration of enemy motors. As soon as a plane came within range the tuning fork would pick up the vibration, and the warning would be relayed immediately to points farther in the rear.

On the evening of September 3 an attempt by the Germans to raid the English coast was made but it was successfully repulsed by the coast defense guns. The foliowing day, about noon, a photographic scouting plane came over our area. The weather was clear and the air crisp, thus making ideal conditions for photographic work. The anti-aircraft guns, both mobile and stationary, did valuable work in keeping the plane at a very high altitude. Some criticism was heard concerning Colonel Patterson’s desire to have the Stars and Stripes flying over the hospital area from such a tall flag pole. It is believed by some to be possible that a photograph of this camp, showing the United States flag flying overhead, was secured and that, as a warning to other Americans who were to follow us into the battlefields of France, we should be made the objective of an aerial attack in spite of the fact that we were a hospital unit and therefore classified as noncombatants.

Be that as it may, we know not what was in the minds of the Germans when, in the evening of September 4, they dispatched their mission of death, having as their objective an American Base Hospital caring for two thousand sick and wounded patients.

There had been an attempted raid on the English coast earlier in the evening which had apparently failed. At 10:30 we received a warning that enemy planes were approaching along the coast. The anti-aircraft guns at Sainte Cecile Plage and at Neufchatel were actively employed for a few minutes but were soon quiet and the all-clear was sounded. At 10:55 p.m., without any warning whatsoever, and while all lights in the vast twelve thousand bed hospital area were illuminating the camp, an enemy aeroplane suddenly swooped down over the brim of the circle of high bills from the direction of Etaples. A few minutes prior to this incident a loud report as of the crashing of a bomb had been heard from that direction, but by those who had heard it, it was mistaken for the report of an anti-aircraft battery.

Lieutenant William Fitzsimmons, who had recently been appointed adjutant of Base Hospital No. 5, was among those who heard the first report, and fearing the possible approach of enemy planes had summoned the sentry, Private Hiram Brewer, to ascertain the cause of the violent explosion. Having answered the question of the adjutant, the guard resumed the patrol of his post. Scarcely a minute had elapsed when another more violent explosion occurred, caused by the dropping of an aerial torpedo on General Hospital No. 18. Fortunately no damage was done as it dropped in the center of the athletic field tearing a deep hole several yards in diameter. Then swinging his plane in a semicircular course, a bomb of the smaller type was dropped into the reception tent of No. 4 General Hospital, followed almost immediately by two bombs that dropped within eighteen inches of each other in front of Lieutenant Fitzsimons’ tent, two others at each end of Ward C-6 and another in the reception tent of No. 11 General Hospital. Lieutenant William Fitzsimmons was instantly killed by the first two bombs to be dropped on Base Hospital No. 5, while the flying fragments wounded Lieutenants Rae Whidden, Thaddeus Smith, Clarence McGuire and Private Hiram Brewer. Fragments from the two bombs which were dropped on Ward C-6 killed Private Oscar Tugo and several patients, while other patients were wounded and large portions of the ward were wrecked.

Written by Rose K. Butler to her sister

September 9, 1917

My dear Anne,

Your last letter came in just fourteen days, good quick work, wasn’t it? Frances said you gave her some of the ‘personal’ messages from one of my letters, and she was quite interested. I‘m very glad it reached you safely; it is nice, too, that they aren’t doing any ‘cutting.‘ Our censor here is quite good, and of course we can send direct to the base censor, which means that the local man does not see what we write. For personal reasons, we rather like this, at time. A new order gives us permission to address the base censor by ordinary envelope instead of the green one which used to be necessary. We leave our letter unsealed, then enclose it in another, sealed and addressed to the base censor. We don’t even have to sign our names now.

You must have had a very lovely vacation and I’m so glad you happened on such a nice place. The cards were most interesting. Several of them I sent in a package I was getting ready for Cousin Charlie who is ‘up the line.‘ He wrote me that writing paper was very scarce, as indeed it is here, so I sent him some with some chocolates and cigarettes.

I did not go to the ‘city’ last week. Passes were held up temporarily and the week was quietly spent for reasons. I don’t know how much has appeared in the papers at home about the present nice little practice of the Hun in aiming bombs at hospitals. The English papers have had quite a bit the last couple of days. Well, we have been bombed — no nurses injured, I’ll say at once. And I think it’s just as well to tell it all, for the accounts were rather inaccurate. We are allowed to mail details after a week’s time.

Several times in our stay here we have seen anti-aircraft shells bursting around an enemy plane at night. The approach of hostile aircraft is signaled by the electric lights, which flash twice and then go out. Three nights in succession, at the same hour, this happened. The third night, the lights came on again so we thought it was a false alarm and went to bed. An hour or so later, out they went again. I was asleep, of course, when Miss L. spoke and said she had heard two reports like heavy gunfire or bombs. I listened and could just catch the humming of the plane. Almost at once, the bombs came down, swishing like rockets and the sound when they struck the earth carried me back to the summer in Wellesley when the oaks in the valley were struck; do you remember? Of course it was all confusion for a few minutes for no one knew where they had struck, though some of the girls saw them fall. Two hit just behind the officers’ tents, which are across the way from our quarters and perhaps a couple of hundred yards distant. Here one officer was killed, and two were wounded — all new men recently attached to us.

Two more bombs fell among the tents further away. In one were the boys on guard duty; three more killed and several injured. The last fell in a tent ward. One patient was killed and several injured with one dying the next day. My ward was next in line but thank Heavenl! the supply of bombs seemed to be exhausted. One of my boys was hurt by a piece of shrapnel. The night nurse in the tent that was struck had a wonderful escape and covered herself with glory. She happened to be outside the tent at the time and rushed right in without a thought of herself. When she got time to take stock, she found her clothes fairly riddled and her watch shot away, but got only a small bruise under one eye. She is a tiny, pale red-haired little thing who looks as if a mouse would scare her. You can‘t always tell.

I don’t think we were much frightened. Miss L. and I did not even go out of our room. The operating room, of course, was full of people and we felt we had no right to go back on the ward unless we were needed.

Since then, we have felt as we did on ship board and in London; our windows must allow no gleam of light to pass. I hardly think they will trouble us again, we did think they would probably retum next night in force, but a providential storm came up which continued most of the night and to think we even cavilled at the rain! There hasn’t been another really good night and by now they’ve probably been diverted in other directions. I think I shall dislike moonlight for a long time— that glorious calm, golden night and those fiery things dropping from a machine so high that no one even saw it! There is no word but ‘hellish’ for it.

Well, Miss L. and 1 with the Matron and the Night Matron went to the funeral on the morning of the second day after. My friend Ross had told me quite a bit about a military funeral so I knew in a way what to expect, but I shall never forget a detail of that one. I’m very glad I went.

Officers and ‘Sisters‘ had a ohar-a-banc to go in; the cemetery is three or four miles south of south of us. We stood about for a few minutes until the procession formed, then went in slow march time down the slope into the cemetery. A Kiltie led playing a dirge on the bagpipes. Behind him walked two Scotch buglers. Next came the two chaplains, Roman Catholic and ours, then an escorting squad of our men and after them the bodies of the four Americans, each coffin on a sort of two-wheeled stretcher with six men escorting, each coffin was covered with an American flag and heaped with flowners — asters, gladioli, phlox, etc. and great masses of goldenrod. Then came the rest of the escort; our officers followed and the ‘Sisters‘ after them — from the Chicago Unit, from K. H.’s from the British hospitals and the Canadian in the neighborhood, and with them a number of V.A.D.’s. Our own men followed and somewhere in the procession were officers from all these places and from the base — American, English, Scotch and Canadian. I sort of lost track of the rest of the procession but it was an amazingly large crowd. I wish I could describe it — all those uniforms of one sort and another — the cemetery a blaze of color, with nasturtiums, marigolds, etc. everywhere.

On our left, going down, is the officers’ section. The graves are regular oblongs in rows, each marked by a small wooden cross at the head, with name, number, regiment, etc. stamped on little metal strips and nailed on while a stake at the foot has the number and letter of the grave. On the right are the men, only with two crosses at the head of each grave, for they are buried two together. The bagpipes wailed until we reached Capt. Fitzsimons’ grave. He was a Catholic and there had been a mass at eight for him. The Catholic chaplain, in his khaki, took off his cap and put his hands around his neck and read the service and our chaplain acted as his altar boy! In all the funerals that place has seen, surely there has never been before just that combination that day brought.

At the end, when the flowers and flag had been laid aside, the poor cheap coffin lowered, the buglers standing together at the head of the grave played the ‘Last Post.’ The bagpipes began again and we marched over to the other side where our chaplain read the service for our three boys. I didn’t say that besides the tremendous crowd in the cemetery, there were groups in the kilts and khaki on the dunes and in the pine groves and quite a lot of peasants and an old gaunt French padre. Truly a strange and weird experience.